Beyond the Bible

Before I begin, I want to mention that this commentary is a response to David Neff's report of the book by I. Howard Marshall entitled "Beyond the Bible". I have not read this book myself and my comments are based merely on what I construe from Mr. Neff's article.

First, let's reason about who or what God is. I've already spelled out some thought about temporality and eternity.

Ontology and teleology and other such classical "proofs" of God are not true proofs per se, but they are self-evident truths (to the extent that one's brain doesn't hurt too much to contemplate them). Rather than proving the existence of God, they offer a preliminary definition of God as foundational to the existence of the temporal universe. In other words, The temporal, measurable universe is rooted in that which is eternal and immeasurable. In Biblical terms, "In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth." Therefore, we ascribe the term "God" to that which is eternal and immeasurable.

Our ideas about who God is do not originate in a vacuum. To some degree, they come from our experiences and observations of the world in which we live as viewed through the filter of our temperament. To another degree, they must come from God Himself.

But one must ask, is God sentient? One test is to ask if there is something obviously intentional built into the universe that can only be ascribed to God? If it is possible for the eternal to exist without the existence of the temporal, then the existence of the temporal is enough to prove deductively that God functions intentionally. Therefore, God is sentient. If we as temporal beings are sentient, how could we be created by a God that is not sentient? The answer is as self-evident as the existence of the eternal. One must also conclude that if God is intentional in our creation, then He has a purpose for us. We are not our own.

If God has a purpose for us, by what means does He communicate this purpose to us? The communication must be widely accepted as communication from God. After all, why would the creator communicate through an obscure means? Since widespread communication can be duplicated, it stands to reason that the communication would be set apart from any counterfeit communication by some measurable means. Holy Scriptures are obviously the communication that is widely accepted. Holy Scriptures are also widely counterfeited. If Holy Scriptures in every religion agreed with one another, then we could not say that one is right and the rest are wrong. They do not all agree. Therefore, one must be right and the rest counterfeit.

There is one set of holy Scriptures that stands out. It was written by several authors over a period of a couple thousand years with a unified message. It was written in a context of historical congruity. Documentation of it's transmission from ancient copies to more recent copies demonstrates a remarkable lack of error. The overwhelming abundance of it's copies throughout the ages is astonishing. Perhaps the greatest earmark is the accuracy of fulfilled SPECIFIC prophesies of future events. None have proven false. The only prophesies left unfulfilled are the eschatological ones which wouldn't have happened yet.

This earmarked communication consists of the Hebrew Scriptures and their fulfillment in the Christian Scriptures. This is the Christian Bible.

Theology is the study of who God is. Hermeneutics is the study of the Bible in order to develop our knowledge base for theology. We may start with ideas gained from experiences and observations, but ultimately we must refine these ideas if not supplant them entirely with truth gained from hermeneutics.

What do we make of how different people and different traditions interpret the Bible? Is there a right way and a wrong way to do hermeneutics? If so, then how do we know what the right way is? Just like the Bible is earmarked as God's communication to us, certain hermeneutical principles can be derived from the same apologetic that leads us to look for God's earmarked communication. For example, if God wants to communicate to us, His communication will use language that is understandable. It will employ expressions of speech and cultural references that are known and researchable.

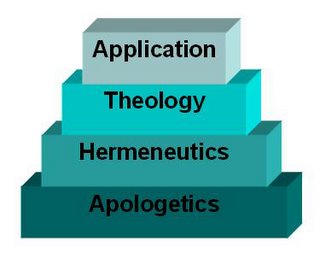

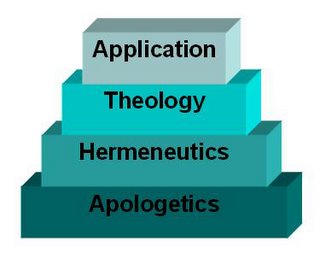

So, I've briefly discussed that good Christian hermeneutics have a sound and reasonable apologetic and that good theological principles are discerned from applying sound hermeneutical principles to the Bible. This is not the end of Biblical study, however. The purpose is not simply to know about God. Instead, if we go back to our apologetic, we realize that God want us to know His purpose for us. That means that we must apply what we know about God to our current situation. Therefore, application is the crown of the Biblical study pyramid:

This is my understanding of an organization of logical premises and conclusions that create the framework for Biblical studies and analyses. This is why I feel compelled to address the article linked in the title of this post.

The article states:

This appears to presuppose that the only applications we can make from a systematic review of the Bible are those that the Bible itself makes. This view fails to consider that the purpose of the applications made in the Bible is to point us to transcendent principles that may be applied to any situation.

Also, I doubt that thorough study results in inconsistent results. No examples are given here of what these inconsistencies may be. I have found more often that theologians apply hermeneutical principles inconsistently. For example, Lutheran doctrine considers the statement of Christ, "This is my body," to be literal while it denies that the thousand-year reign is literal. To suggest that "this approach" (J.I. Packer's four interpretational principles, which represent foundational areas of traditional hermeneutical principles) does not yield consistent results is antithetical to the apologetical notion of the unified message of the Bible. I suggest, instead, that applying consistent hermeneutical results to the Bible yields exceptionally consistent results. The greatest area of tedium I have found in studying the Bible is when analyzing a text and deciding on the set of hermeneutical principles that apply, going back and checking to see if I have applied this same principle consistently in the formation of other theological principles.

The article continues:

It also states that "The book's title, 'Beyond the Bible', is a recognition that doctrine develops." It uses "the Trinity and the high Christology of Chalcedon" as examples of doctrine that develops writing that "Biblical revelation points us ineluctably toward those truths, but the Bible writers never make them explicit."

I would agree that God uses tradition as well as historic debates to establish certain doctrine. I also agree with the need for discipleship. What is lacking in this analysis is a distinction between extra-Biblical instruction that is correct and that which is erroneous. There must be an overriding principle lest we fall into the trap of theistic existentialism. True doctrine is not developed, it is discovered. False doctrine is developed.

The article makes an interesting distinction claiming that "Evangelicals are often criticized because we tend to emphasize Paul's theology rather than Jesus' ethics. But how do we apply Jesus' words?" Later in the article it comes close to inadvertently answering this question:

Evangelicals should not be criticized for emphasizing Paul (and the other epistles) because they are precisely Christ's teachings as understood within the context of the Hebrew Scriptures as applied to real situations.

One other claim addressed in the article is that "'one cannot make a body of doctrine heresy-proof, because heretics are so ingenious.' Thus, the work of reading and applying Scripture is never done." This implies that new heresies continue to crop up. While I agree that there are a few obscure heresies that have cropped up in more recent times, the big heresies that we are all familiar with are the same old heresies that were directly addressed by the epistle writers. "The work of reading and applying Scripture is never done" is true less because of new heresies, but more because of new Christians.

Also, I take issue with the statement quoted by Neff, "one cannot make a body of doctrine heresy-proof, because heretics are so ingenious." I'm not sure how a context could qualify the meaning of this, so I'm not sure if I'm misunderstanding something by seeing this comment out of context. I have said that true doctrine is discovered and that false doctrine is developed. If we make a body of doctrine, we are not discovering the body of true doctrine that God has given us as much as we are construing a false body of true and/or false doctrines. Therefore, if we are making a body of doctrine it will not be heresy-proof. If we discover the body of true doctrine God has given us, then it is error-proof. Heretics will deny the body of true doctrine, therefore it is not the body of doctrine that needs to be error-proof, but the heretic that needs to be brought into subjection of the doctrine God has given us. The heretic does not hold the body of true doctrine, but a false body of doctrine that he has made.

The last statement of the article is as vague a well-written statement as I've ever read:

The question I have is if the rules for interpreting Scripture only take us so far, what rules do Msrrs. Neff and Marshall suggest will take us farther? Perhaps they are in the book.

First, let's reason about who or what God is. I've already spelled out some thought about temporality and eternity.

Ontology and teleology and other such classical "proofs" of God are not true proofs per se, but they are self-evident truths (to the extent that one's brain doesn't hurt too much to contemplate them). Rather than proving the existence of God, they offer a preliminary definition of God as foundational to the existence of the temporal universe. In other words, The temporal, measurable universe is rooted in that which is eternal and immeasurable. In Biblical terms, "In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth." Therefore, we ascribe the term "God" to that which is eternal and immeasurable.

Our ideas about who God is do not originate in a vacuum. To some degree, they come from our experiences and observations of the world in which we live as viewed through the filter of our temperament. To another degree, they must come from God Himself.

But one must ask, is God sentient? One test is to ask if there is something obviously intentional built into the universe that can only be ascribed to God? If it is possible for the eternal to exist without the existence of the temporal, then the existence of the temporal is enough to prove deductively that God functions intentionally. Therefore, God is sentient. If we as temporal beings are sentient, how could we be created by a God that is not sentient? The answer is as self-evident as the existence of the eternal. One must also conclude that if God is intentional in our creation, then He has a purpose for us. We are not our own.

If God has a purpose for us, by what means does He communicate this purpose to us? The communication must be widely accepted as communication from God. After all, why would the creator communicate through an obscure means? Since widespread communication can be duplicated, it stands to reason that the communication would be set apart from any counterfeit communication by some measurable means. Holy Scriptures are obviously the communication that is widely accepted. Holy Scriptures are also widely counterfeited. If Holy Scriptures in every religion agreed with one another, then we could not say that one is right and the rest are wrong. They do not all agree. Therefore, one must be right and the rest counterfeit.

There is one set of holy Scriptures that stands out. It was written by several authors over a period of a couple thousand years with a unified message. It was written in a context of historical congruity. Documentation of it's transmission from ancient copies to more recent copies demonstrates a remarkable lack of error. The overwhelming abundance of it's copies throughout the ages is astonishing. Perhaps the greatest earmark is the accuracy of fulfilled SPECIFIC prophesies of future events. None have proven false. The only prophesies left unfulfilled are the eschatological ones which wouldn't have happened yet.

This earmarked communication consists of the Hebrew Scriptures and their fulfillment in the Christian Scriptures. This is the Christian Bible.

Theology is the study of who God is. Hermeneutics is the study of the Bible in order to develop our knowledge base for theology. We may start with ideas gained from experiences and observations, but ultimately we must refine these ideas if not supplant them entirely with truth gained from hermeneutics.

What do we make of how different people and different traditions interpret the Bible? Is there a right way and a wrong way to do hermeneutics? If so, then how do we know what the right way is? Just like the Bible is earmarked as God's communication to us, certain hermeneutical principles can be derived from the same apologetic that leads us to look for God's earmarked communication. For example, if God wants to communicate to us, His communication will use language that is understandable. It will employ expressions of speech and cultural references that are known and researchable.

So, I've briefly discussed that good Christian hermeneutics have a sound and reasonable apologetic and that good theological principles are discerned from applying sound hermeneutical principles to the Bible. This is not the end of Biblical study, however. The purpose is not simply to know about God. Instead, if we go back to our apologetic, we realize that God want us to know His purpose for us. That means that we must apply what we know about God to our current situation. Therefore, application is the crown of the Biblical study pyramid:

This is my understanding of an organization of logical premises and conclusions that create the framework for Biblical studies and analyses. This is why I feel compelled to address the article linked in the title of this post.

The article states:

"Marshall says this approach is inadequate because it does not yield consistent results, and because it provides little help in dealing with contemporary problems that could not have been foreseen by the biblical writers."

This appears to presuppose that the only applications we can make from a systematic review of the Bible are those that the Bible itself makes. This view fails to consider that the purpose of the applications made in the Bible is to point us to transcendent principles that may be applied to any situation.

Also, I doubt that thorough study results in inconsistent results. No examples are given here of what these inconsistencies may be. I have found more often that theologians apply hermeneutical principles inconsistently. For example, Lutheran doctrine considers the statement of Christ, "This is my body," to be literal while it denies that the thousand-year reign is literal. To suggest that "this approach" (J.I. Packer's four interpretational principles, which represent foundational areas of traditional hermeneutical principles) does not yield consistent results is antithetical to the apologetical notion of the unified message of the Bible. I suggest, instead, that applying consistent hermeneutical results to the Bible yields exceptionally consistent results. The greatest area of tedium I have found in studying the Bible is when analyzing a text and deciding on the set of hermeneutical principles that apply, going back and checking to see if I have applied this same principle consistently in the formation of other theological principles.

The article continues:

"You can't learn to play tennis without observing, practicing, and having a coach. Likewise, you can't understand how the discrete moments of revelation in the Bible become Christian doctrine without observing the work of those who went before, personally engaging in the active interpretation and application of the text, and having a 'coach.'"

It also states that "The book's title, 'Beyond the Bible', is a recognition that doctrine develops." It uses "the Trinity and the high Christology of Chalcedon" as examples of doctrine that develops writing that "Biblical revelation points us ineluctably toward those truths, but the Bible writers never make them explicit."

I would agree that God uses tradition as well as historic debates to establish certain doctrine. I also agree with the need for discipleship. What is lacking in this analysis is a distinction between extra-Biblical instruction that is correct and that which is erroneous. There must be an overriding principle lest we fall into the trap of theistic existentialism. True doctrine is not developed, it is discovered. False doctrine is developed.

The article makes an interesting distinction claiming that "Evangelicals are often criticized because we tend to emphasize Paul's theology rather than Jesus' ethics. But how do we apply Jesus' words?" Later in the article it comes close to inadvertently answering this question:

"The epistles are responses to moral, spiritual, or theological errors. These letters did not attempt to set out truth in a systematic way, but to apply truth to wayward communities. Marshall shows how the apostles appealed to the leadership of the Spirit, the consistent teaching of the church since the time of Jesus, and the way in which the events of Jesus' life, death, and resurrection opened up their understanding of the Scriptures."

Evangelicals should not be criticized for emphasizing Paul (and the other epistles) because they are precisely Christ's teachings as understood within the context of the Hebrew Scriptures as applied to real situations.

One other claim addressed in the article is that "'one cannot make a body of doctrine heresy-proof, because heretics are so ingenious.' Thus, the work of reading and applying Scripture is never done." This implies that new heresies continue to crop up. While I agree that there are a few obscure heresies that have cropped up in more recent times, the big heresies that we are all familiar with are the same old heresies that were directly addressed by the epistle writers. "The work of reading and applying Scripture is never done" is true less because of new heresies, but more because of new Christians.

Also, I take issue with the statement quoted by Neff, "one cannot make a body of doctrine heresy-proof, because heretics are so ingenious." I'm not sure how a context could qualify the meaning of this, so I'm not sure if I'm misunderstanding something by seeing this comment out of context. I have said that true doctrine is discovered and that false doctrine is developed. If we make a body of doctrine, we are not discovering the body of true doctrine that God has given us as much as we are construing a false body of true and/or false doctrines. Therefore, if we are making a body of doctrine it will not be heresy-proof. If we discover the body of true doctrine God has given us, then it is error-proof. Heretics will deny the body of true doctrine, therefore it is not the body of doctrine that needs to be error-proof, but the heretic that needs to be brought into subjection of the doctrine God has given us. The heretic does not hold the body of true doctrine, but a false body of doctrine that he has made.

The last statement of the article is as vague a well-written statement as I've ever read:

"The rules for interpreting Scripture can take us only so far, but as Marshall and Vanhoozer demonstrate, we can learn a lot by watching great interpreters playing at their finest."

The question I have is if the rules for interpreting Scripture only take us so far, what rules do Msrrs. Neff and Marshall suggest will take us farther? Perhaps they are in the book.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home